Details About US Settler-to-Corporate Terrorism Images

Lt. Colonel (ret) Military Historian Dr. John Grenier: “In the frontier wars between 1607 and 1814, Americans forged two elements—unlimited war and irregular war—into their first way of war…. U.S. people are taught that their military culture does not approve of or encourage targeting and killing civilians and know little or nothing about the nearly three centuries of warfare—before and after the founding of the U.S.—that reduced the Indigenous peoples of the continent to a few reservations by burning their towns and fields and killing civilians, driving the refugees out—step by step—across the continent…. [V]iolence directed systematically against non-combatants through irregular means, from the start, has been a central part of Americans’ way of war.” The First Way of War, American War Making on the Frontier, 1607-1814 (isbn.nu, 2008, pp. 10, 223-24) Corporate Historian Richard Grossman: “As the 19th Century began, constitutions, laws and customs in the new United States denied the overwhelming majority of humans standing and equality before the law, along with authority to vote. As the 19th Century ended, legislative laws, judge-made laws, propaganda, armed might and persistent violence by the corporate class had transformed the United States from a minority-ruled Slave Nation into a minority-ruled Corporate Nation. This despite valiant mass resistance and magnificent people’s struggles. The emerging Corporate State – like the previous Slave State – was impressively constitutionalized.” An Act To Criminalize Chartered, Incorporated Business Entities (2011)

US Settler-to-Corporate Terrorism Details

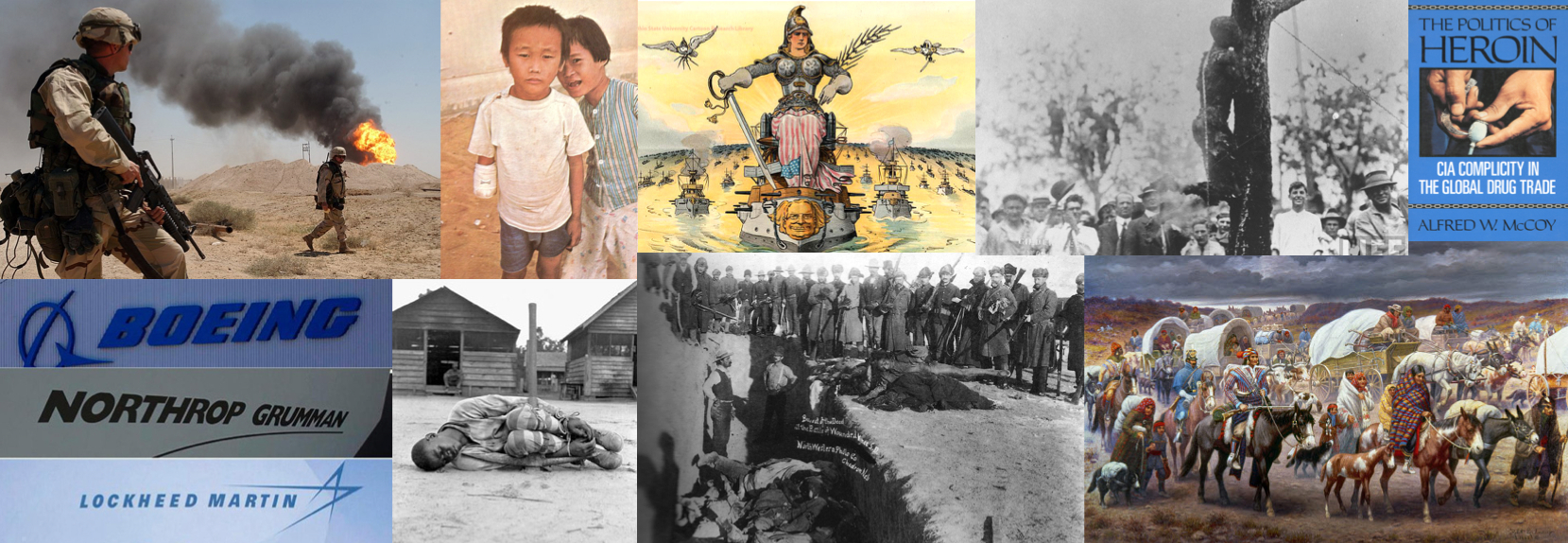

- Burning Iraq Oil, 2003 — LINK Southern, Iraq (Apr. 2, 2003) — U.S. Army Sgt. Mark Phiffer stands guard duty near a burning oil well in the Rumaylah Oil Fields in Southern Iraq.

- The Children of Vietnam — LINK William F. Pepper 1967: “Any visitor to a hospital, an orphanage, a refugee camp, can plainly see the evidence of reliance on amputation as a surgical shortcut.” (page 13) “Napalm, and its more horrible companion, white phosphorus, liquidize young flesh and carve it into grotesque forms. The little figures are afterward often scarcely human in appearance, and one cannot be confronted with the monstrous effects of the burning without being totally shaken. Perhaps it was due to a previous lack of direct contact with war, but I never left the tiny victims without losing composure. The initial urge to reach out and soothe the hurt was restrained by the fear that the ash-like skin would crumble in my fingers…. It is a ghastly situation. And triply compounded is the ghastliness of napalm and phosphorus. Surely, if ever a group or children in the history of man, anywhere in the world, had a moral claim for their childhood, here they are. Every sickening, frightening scar is a silent cry to Americans to begin to restore that childhood for those whom we are compelled to call our own because of what has been done in our name.”

- “Peace” Columbia in full war regalia, 1905 — LINK Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz: “The Columbus myth suggests that from US independence onward, colonial settlers saw themselves as part of a world system of colonization. ‘Columbia,’ the poetic, Latinate name used in reference to the United States from its founding throughout the nineteenth century, was based on the name of Christopher Columbus. The ‘Land of Columbus’ was—and still is—represented by the image of a woman in sculptures and paintings, by institutions such as Columbia University, and by countless place names, including that of the national capital, the District of Columbia.” An Indigenous Peoples’s History of the United States, (page 4)

- Depths of U.S. White Supremacy — LINK How the NAACP fought lynching with pictures of a man being lynched; Nothing was censored and that was the point Map of White Supremacy mob violence, 1835-1964, The lynchings and riots to enforce racial superiority in the US

- The Politics of Heroin: CIA Complicity In The Drug Trade, second edition (1991) — LINK by Alfred McCoy, 1972 first edition sources: hyper-text, PDF; on Nugan Hand Bank, pages 461-472 of 1991 edition. 2003 third edition, The Politics of Heroin: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade, Afghanistan, Southeast Asia, Central America, Columbia: The first book to prove CIA and U.S. government complicity in global drug trafficking, The Politics of Heroin includes meticulous documentation of dishonesty and dirty dealings at the highest levels from the Cold War until today. Maintaining a global perspective, this groundbreaking study details the mechanics of drug trafficking in Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and South and Central America. New chapters detail U.S. involvement in the narcotics trade in Afghanistan and Pakistan before and after the fall of the Taliban, and how U.S. drug policy in Central America and Colombia has increased the global supply of illicit drugs.

- Merchants of Death, Capitalism’s back bone: Boeing Northrop Grumman Lockheed Martin — LINK Merchants of Death: Raytheon and Boeing Supply “The Islamic State” (ISIS) (2015) The REAL Cost of the War of Terror, 2016 Divest from the War Machine

- 20th Century Slavery in the U.S. — LINK 1930s forced labor camp in the South Slavery Today from Free The Slaves

- Wounded Knee, Lakota Mass Grave, 1891 — LINK Bodies beings dumped into a mass grave at Wounded Knee. Between 150-300 Lakota men, women and children were killed by U.S Cavalry. Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz: U.S. Settler-Colonialism and Genocide Policies against Native Americans: “US policies and actions related to Indigenous peoples, though often termed ‘racist’ or ‘discriminatory,’ are rarely depicted as what they are: classic cases of imperialism and a particular form of colonialism—settler colonialism. As anthropologist Patrick Wolfe writes, ‘The question of genocide is never far from discussions of settler colonialism. Land is life—or, at least, land is necessary for life.’ The history of the United States is a history of settler colonialism.” (2016) “Indian” Wars: “The integral link between Wounded Knee in 1890 and Wounded Knee in 1973 suggests a long-overdue reinterpretation of indigenous-US relations as a template for US imperialism and counterinsurgency wars. As Vietnam veteran and author Michael Herr observed, we ‘might as well say that Vietnam was where the Trail of Tears was headed all along, the turnaround point where it would touch and come back to form a containing perimeter.’ Seminole Nation Vietnam War veteran Evan Haney made the comparison in testifying at the Winter Soldier Investigations: ‘The same massacres happened to the Indians . . . I got to know the Vietnamese people and I learned they were just like us . . . I have grown up with racism all my life. When I was a child, watching cowboys and Indians on TV, I would root for the cavalry, not the Indians. It was that bad. I was that far toward my own destruction.’ As it happened, the fifth anniversary of the My Lai massacre in Vietnam occurred at the time of the 1973 siege of Wounded Knee. It was difficult to miss the analogy between the 1890 Wounded Knee massacre and My Lai, 1968. Alongside the front-page news and photographs of the Wounded Knee siege that was taking place in real time were features with photos of the scene of mutilation and death at My Lai.” (2014)

- Trail of Tears — LINK Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz: An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, pp. 112-114 (2014): “The 1838 forced march of the Cherokee Nation, now known as the Trail of Tears, was an arduous journey from remaining Cherokee homelands in Georgia and Alabama to what would later become northeastern Oklahoma. After the Civil War, journalist James Mooney interviewed people who had been involved in the forced removal. Based on these firsthand accounts, he described the scene in 1838, when the US Army removed the last of the Cherokees by force:

“Under [General Winfield] Scott’s orders the troops were disposed at various points throughout the Cherokee country, where stockade forts were erected for gathering in and holding the Indians preparatory to removal. From these, squads of troops were sent to search out with rifle and bayonet every small cabin hidden away in the coves or by sides of mountain streams, to seize and bring in as prisoners all the occupants, however or wherever they might be found. Families at dinner were startled by the sudden gleam of bayonets in the doorway and rose up to be driven with blows and oaths along the weary miles of trail that led to the stockade. Men were seized in their fields or going along the road, women were taken from their wheels and children from their play. In many cases, on turning for one last look as they crossed the ridge, they saw their homes in flames, fired by the lawless rabble that followed on the heels of the soldiers to loot and pillage. So keen were these outlaws on the scene that in some instances they were driving off the cattle and other stock of the Indians almost before the soldiers had fairly started their owners in the other direction. Systematic hunts were made by the same men for Indian graves, to rob them of the silver pendants and other valuables deposited with the dead. A Georgia volunteer, afterward a colonel in the Confederate service, said: ‘I fought through the civil war and have seen men shot to pieces and slaughtered by thousands, but the Cherokee removal was the cruelest work I ever knew.’ ” (Mooney, p.130)

“Half of the sixteen thousand Cherokee men, women, and children who were rounded up and force-marched in the dead of winter out of their country perished on the journey. “The Muskogees and Seminoles suffered similar death rates in their forced transfer, while the Chickasaws and Choctaws lost around 15 percent of their people en route. An eyewitness account by Alexis de Tocqueville, the French observer of the day, captures one of thousands of similar scenes in the forced deportation of the Indigenous peoples from the Southeast:

“I saw with my own eyes several of the cases of misery which I have been describing; and I was the witness of sufferings which I have not the power to portray. “At the end of the year 1831, whilst I was on the left bank of the Mississippi at a place named by Europeans Memphis, there arrived a numerous band of Choctaws (or Chactas, as they are called by the French in Louisiana). These savages had left their country, and were endeavoring to gain the right bank of the Mississippi, where they hoped to find an asylum which had been promised them by the American government. It was then the middle of winter, and the cold was unusually severe; the snow had frozen hard upon the ground, and the river was drifting huge masses of ice. The Indians had their families with them; and they brought in their train the wounded and sick, with children newly born, and old men upon the verge of death. They possessed neither tents nor wagons, but only their arms and some provisions. I saw them embark to pass the mighty river, and never will that solemn spectacle fade from my remembrance. No cry, no sob was heard amongst the assembled crowd; all were silent. Their calamities were of ancient date, and they knew them to be irremediable. The Indians had all stepped into the bark which was to carry them across, but their dogs remained upon the bank. As soon as these animals perceived that their masters were finally leaving the shore, they set up a dismal howl, and, plunging all together into the icy waters of the Mississippi, they swam after the boat.” (Tocqueville, search on power to portray)“In his biography of Jackson, Rogin points out that this was no endgame: ‘The dispossession of the Indians … did not happen once and for all in the beginning. America was continually beginning again on the frontier, and as it expanded across the continent, it killed, removed, and drove into extinction one tribe after another.’ “Against all odds, some Indigenous peoples refused to be removed and stayed in their traditional homelands east of the Mississippi. In the South, the communities that did not leave lost their traditional land titles and status as Indians in the eyes of the government, but many survived as peoples, some fighting successfully in the late twentieth century for federal acknowledgment and official Indigenous status. In the north, especially in New England, some states had illegally taken land and created guardian systems and small reservations, such as those of the Penobscots and Passamaqpoddies in Maine, both of which won lawsuits against the states and attained federal acknowledgment during the militant movements of the 1970s. Many other Native nations have been able to increase their land bases.”